On the Road at 60

By John Leland

October, 2017

A few thoughts about Jack Kerouac’s “On the Road” at 60:

The earliest events in the book take place in 1947, which means they are as close to the end of the Reconstruction Era as they are to us today. After some false starts, Kerouac wrote the famous scroll draft in 1951, which also puts it nearer to the 19th century than to the present, and even the final version, which came out in September 1957, precedes not just the internet and cellphones but the statehood of Alaska and Hawaii. “On the Road” has lasted longer than Kerouac, who died at 47, or Neal Cassady, who died just short of 42.

How, then, should we read the book at 60, old enough to be hunted down by AARP?

One possible answer is that we shouldn’t. Maybe in 2017 there’s no place for a book that accepts beating women, celebrates drunken sex with underage Mexican prostitutes or blithely romanticizes the “old Negro cotton picker.”

But what strikes me this year, with so much ethnic and political sectarianism in the air, is how much of the book involves Sal Paradise, the narrator, seeking out and learning from people who are different from him.

Unlike a lot of literary travelers, he doesn’t leave home in search of himself. He’s not Dorothy discovering that there’s no place like home. His clan or tribe have gotten him where he is at the book’s start, with a busted marriage and a mourned father, “and the feeling that everything was dead.”

His remedy is to leave the silo behind, to expose himself to the breadth of humanity. Kerouac once described “On the Road” as a search for God – “and we found him,” he wrote – but Sal is most conspicuously curious about people: how they talk, love, dream and make peace with themselves. One of his first acts on the road is to give a heavy wool shirt to a fellow traveler named Eddie. He’s a student, a vacuum for knowledge, delighting in the lore and speech of hoboes, truckers, drifters, cons, hipsters, African Americans, jazz musicians and working stiffs. Almost never do his encounters involve an exchange of money. Sal travels through the book without fear or suspicion, grateful for any glimpse of a world different from his own. There are virtually no conflicts in the book, because Sal gains something of value from almost everyone he meets. And as he learns, he grows.

Dean Moriarty, of course, is his immediate opposite: impulsive, sexually confident, western, a doer, not a watcher. He’s so different that at first Sal can see him only as a mythic archetype, “a young Gene Autry – trim, thin-hipped, blue-eyed, with a real Oklahoma accent – a sideburned hero of the snowy West.” This distance sets the book in motion, with Dean as both its grail and its engine. But over the course of the novel, Sal begins to see Dean in a different light, as the flawed, all-too-human character who fails his wives and children and abandons Sal on a sickbed in Mexico.

Sal, by contrast, is barely a shadow of a character, in part because he is least interested in himself. The book’s two best-known passages are about him trying to get out of his own skin: in one, shambling after the “mad ones, the ones who are mad to live, mad to talk, mad to be saved;” and in the other, walking in “lilac evening” through Denver’s black neighborhood, “wishing I were a Negro” or a “Denver Mexican, or even a poor overworked Jap, anything but what I was so drearily, a ‘white man’ disillusioned.”

The first passage appears at the very beginning of the book, before Sal begins his education; the second falls in the middle, just before Sal’s perception of Dean starts to change. He’s still seeing in archetypes or stereotypes, which makes the passage discomfiting to read now.

But it’s not the final Sal. As a traveler, he goes from viewing America through a map, plotting out a disastrous route to take him cross country, to knowing the landscape firsthand. And the same with its people. By the time Sal heads home from his last journey, after Dean abandons him, his mind is clear and he’s ready to tell his story. “I heard the sound of footsteps from the darkness beyond, and lo, a tall old man with flowing white hair came clomping by with a pack on his back, and when he saw me as he passed, he said, ‘Go moan for man,’ and clomped back to his dark.”

This is the permission the writer has sought all along. He’s ready to write “On the Road,” with all its characters and voices, its topography and tribulations. The story is not just his own, but that of all the people he met along the way: wiser for their input, open to their differences, as bumpy and multi-hued as the land itself.

He’s not a perfect student. Some of his female or non-white characters are less than fully-developed individuals. But in these days of border walls and identity politics, of perceptions that strangers who are not like “us” should be kept out or at bay, there’s something refreshing about a book that says that the way to learn and grow is to hop in a stranger’s car and listen and watch.

After 60 years, the road keeps going.

—

John Leland is a Metro reporter for The New York Times. Since joining The Times in 2000, he has covered topics ranging from the poetry of rock lyrics to the housing crisis. He is the author of two books: Hip: The History (HarperCollins, 2004), a cultural history of hipness, and Why Kerouac Matters: The Lessons of “On the Road” (They’re Not What You Think) (Viking, 2007).

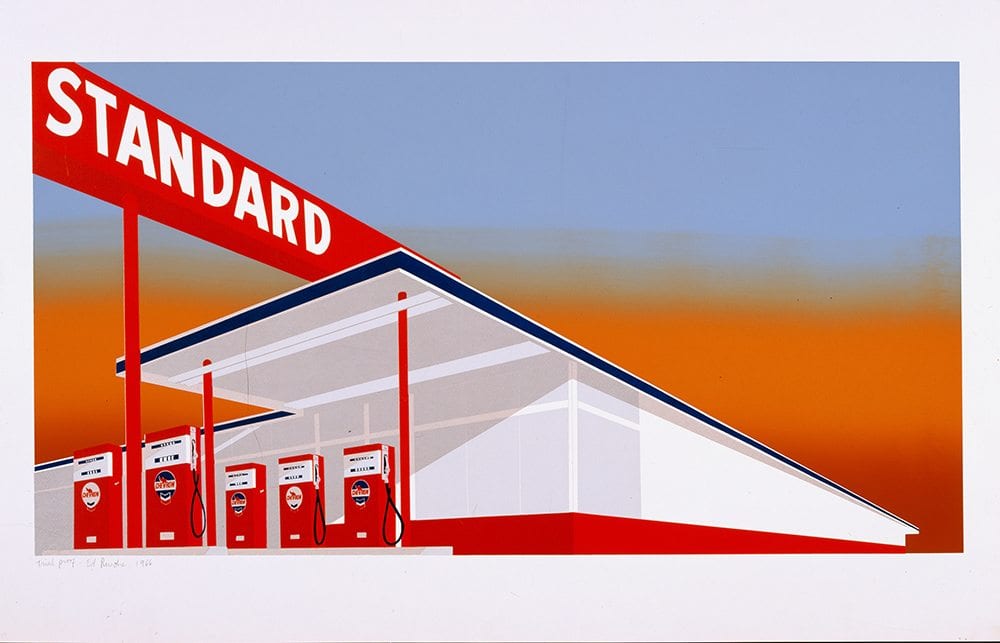

Image: Ed Ruscha, “Standard Station, Amarillo, Texas,” 1966 (accessed at http://www.sfexaminer.com/an-american-road-trip-inspired-ed-ruscha-works/)