The Reception of Jack Kerouac in Spain.

In the early 1950s, when Jack Kerouac began to publish his first works in the United States, Spain had already been under the yoke of a dictator, General Francisco Franco, for nearly twenty years. Publications and the culture in general were controlled by censorship. Franco’s dictatorship was inspired by fascism in Italy and Germany, but with strict added morals of the Catholic Church. Inspired by Italian and German fascist regimes and adding staunch Roman Catholicism, the Franco regime controlled Spain’s cultural sphere through heavily censoring publications. Given their unconventional ideas, authors like Kerouac were deemed inappropriate and denied publication in Spain. However, the 1960s brought key cultural changes, along with economic development and citizen demands for greater freedom, which made the diffusion of such an important figure in mass culture as Jack Kerouac possible. As the Francoist government began scaling back totalitarian censorship practices, the door opened for renegade thinkers, like Kerouac, to make an impact on the Spanish people. In this article I explore the economic, political, social, and cultural landscape of Francoist Spain, its relation to the publication and censorship of Jack Kerouac’s works, and the impact and legacy Kerouac ultimately left on Spanish culture.

The Franco Dictatorship in the 60s

According to Paul Preston, a leading scholar on the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) and the Franco dictatorship (1939-1975), Franco’s policies were terrible for Spain. This forty-year period was arguably one of the worst moments in Spanish history. Franco, a life-long military man, was dissatisfied with the Second Spanish Republic (1931-1939) and wanted to see Spain return to a more traditional form of government such as a monarchy.

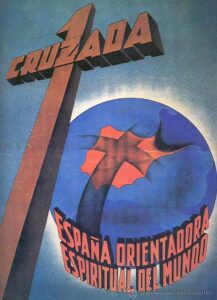

Using conservative and religious ideology, he portrayed his cause as a holy crusade to save the Spanish people from the evils of communism, freemasonry, and the Jewish influence. To create a visual link between himself and the Christian Messiah, Franco went out into the street under a canopy as the Monstrance (a receptacle which holds the Eucharist, or Body of Christ).

Franco’s dictatorship starkly diverged from the Second Spanish Republic. The Republic was an episode of great social and cultural advances, where touring theatres flooded the streets of cities and towns (such as the one founded by the poet and playwright Federico Garcia Lorca, “La Barraca,” that represented the works of Lope de Vega, Calderón de la Barca or Miguel de Cervantes) and the education of the people was a fundamental pillar. In contrast, Franco’s dictatorship was marked by repression, fear, censorship, and death.

Franco granted the church a monopoly on education and culture, and by this period, the Catholic values closely aligned with government values, strongly welding the church and state together. For example, Franco and his government wanted the artists who remained in Spain (those who had not been killed in the civil war nor gone into exile), to create their art within the strict limits of the official culture, or in other words, within the limits of the dictatorship’s political and religious ideology.

Ensuring the regime’s ideology was followed, Franco employed this censorship to prevent the diffusion of ideas contrary to those of the regime. The laws on censorship and the ministry that controlled it were, at first, in the hands of the Party of La Falange, Franco’s political organization. During the first years of dictatorship, there was a death penalty.

However, this situation was not maintained throughout the entire dictatorship. While the first two decades of the Francoist era were especially hard for the Spanish population due to the war’s devastation and the government’s tight authoritarian grip, the 1960s presented great opportunities for Spain and things began changing for the better.

Spain is DifferentSpain is Different.

The second period of Francoism, also called “Aperturimso” (openness) began a period of reduced autarchic policies and brought spectacular economic development (the Spanish economic miracle) accompanied by social change. The Minister of Tourism and Information, Manuel Fraga, appointed by Franco in 1962, started a campaign to attract world tourism. With the popular slogan “Spain is different” Fraga tried to present Spain as an exotic and modern country where tourists would enjoy Paella (a rice dish popular in Valencia), bullfighting, and beaches.

The success of Fraga’s campaign was evident in the arrival of hordes of tourists and young rebels, such as the Beatniks, who attracted Spanish youth. The Beatniks also drew attention from the Franco regime because they presented an image contrary to the dictatorship’s values. Magazines and newspapers started talking about the Beatniks as the new, lost generation—a collection of “absurd rebels” eager to “escape the brutal submission to the mediocrity of present-day American society.”

While the Beatniks made many heads turn in Spain, their rebellious vision of life particularly attracted young people with left and progressive values. This demographic began viewing the Beatniks and their ideas as alternative referents to classical Marxist ideas, and soon after their arrival, interest in authors such as Allan Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, and William Burroughs grew.

Examples of headlines from Mediterráneo, Reader's Digest, and Triunfo (click to read captions).

But the slogan “Spain is different’’ also can be used to describe a strange situation in Spain. While military authorities tried presenting an image of the country’s modernity, Spaniards were still being oppressed for their political ideas.

This song of Concha Velasco, a very famous artist in Spain is called “Beatnik,” and describes the love for a rebel Beatnik (click to play video). The song says: “Beatnik, I know that you are not Beatnik, and I want you to follow me, and talk to me, and look at me, and treat me like a Beatnik (...) because I want you to be Beatnik.”While censorship was not as bad in the sixties as it had been in the earlier Francoist years, it was still prevalent; and if the regime wanted to present themselves as highly modern to the larger world, they realized that they had to be laxer with their laws.

A new printing law, “Fraga Law,” was approved in 1962, allowing greater freedom of expression in print media but with respect to the truth, morals, maintenance of order, and (of course) the regime. Although freedom of expression was allowed, any democratic manifestation of freedom was prohibited. Fraga Law also eliminated the compulsory censorship procedure. However, due to the law’s broad and ambiguous terms, many publishers self-censored to avoid the ministry requisitioning their work. It is this fear of censorship that led to a delay in the publication of Kerouac’s works.

Below are examples of the extremely arbitrary criteria presented in Francoist censor reports:

An example of Franco’s censorship in a film, the dress’s neckline is raised and the actor’s bare arms are covered in the censored image.

- Sexual morality: understood as a prohibition of freedom of expression; media and art cannot attack modesty and good customs, and must abstain from references to abortion, homosexuality, and divorce.

- Political opinions

- Use of language considered indecent, provocative, and inappropriate

- Religion

If any publisher did not comply with what the censorship said, The Ministry could, and did, send publishers to court for non-compliance with Fraga Law’s built in the ambiguity. Censorship was a dissuasive way to avoid the diffusion of works that could endanger the dictatorship, which some people consider a sign of the regime’s weakness in the 1960s.

The publication of Jack Kerouac in Spain

Although there are not many studies yet about this, we can find some evidence that some Latin American editions of Kerouac’s works circulated in Spain. It was quite normal the circulation of clandestine books from other countries, especially among left-wing groups and students. The editions from Argentina were very famous, and some of the translations were the one used when Kerouac was finally published in Spain. For example, we can find Desolation Angel (1959), The Dharma Bums (1969) translated by Miguel de Hernani, and published in Editorial Losada, or On the Road (1959), translated by Juan Rodolfo Wilcock and published by Ediciones Sur.

In Spain, Jack Kerouac’s publications were in magazines. For some reason, the censorship was not so harsh on these types of publications. In this way, the magazines were a good instrument to try to see the consequences that the publication of certain controversial authors could have. The magazines in which Kerouac first appeared were Claraboya, La Estafeta Literaria, and Aquelarre.

Claraboya

Established in 1963, Claraboya tried revitalizing Spanish poetry by moving away from the prevailing lyrical tradition and accepting foreign poetry. With only 19 editions published, the magazine closed in 1968 due to censorship pressure.

Dedicated to the poetry of the Beat Generation, the translators of Issue 14 (1967) included the author of the famous Anthology of the Beat Generation (1970), Barnatán.

La estafeta Literaria. Includes Chorus 113, 127 and 146.

La estafeta Literaria was a publication initially marked by its origin and official support of the regime, circumstances that became diluted with the passage of time.

The 433 edition (1969), dedicated a section to Jack Kerouac as a posthumous tribute. There was also an article by the writer Francisco Umbral called “Requiem for the Beat Generation.”

Aquelarre Magazine. Cuadernos de poesía. Includes Chorus 127 (1970).

Regarding editions published in books, these publications would focus on three main publishers: Plaza & Janés, Producciones Editorial and Visor. According to Lobejón Santos there was no massive interest in translating the Beat Generation into Spanish due to censorship and publishers’ fear of losing money. Although the Barnatán edition is the most important anthology of the beat generation published in Spain in the ‘60s, censorship held a precedent that did not encourage translations and publications. The publishers preferred that the censorship conditions were more lax so as not to lose money.

In 1961, 3000 copies of an English edition of On the Road, were imported, despite censorship guidelines that considered the novel contained “some reprehensible passages of an isolated character, typical of the misfit youth in North America, open to a series of voices and scourges in open opposition to a social order.”

This is the list of the Kerouac publications in Spain:

1964: El pueblo y la ciudad (The Town and the City). Editorial Luis Caralt, Barcelona. Translator: Ramon Margalef.

This publication did not imply any censorship.

1967: Els potols mistics (The Dharma Bums). Editorial Proa, Ayama. Translator: Manuel de Pedrolo. (In Catalan).

The reader in charge of qualifying the work authorized it on the condition that certain scenes that attack morality are cut, “as well as one reference to incest, considering that the rest of the text is acceptable as it is a ‘novel for minorities’.” There were 3000 copies.

1968: Angeles de la desolación (Desolation Angels). Editorial Luis Caralt. Barcelona. Translator: Maria del Carmen Azpiazu.

1970: Antología de la “Beat Generation” (Anthology of the Beat Generation). Translator: Marcos Ricardo Barnatán. Editorial Plaza y Janés; Barcelona.

This work collects some of the published translations in cultural magazines including La Estafeta Literaria and Claraboya.

Anthology of the Beat Generation was a bilingual book with a lot of mistakes, but the critiques were very positive. According to Talens (1971:8), this text fills an important gap since the work that tried to present the generation as a coherent nucleus was missing.

The writer Francisco Umbral said the text of Barnatán, belatedly, brought the famous 1950s North American generation to Spain.

The first edition had 3000 copies, the 1972 second edition was also 3000 copies, and the 1977 third edition was 2000 copies. Three editions of a poetry anthology was rare.

Despite his consideration of being the King of the Beats, only 6 pages of this anthology are dedicated to Kerouac. The anthology included four choruses of Mexico City Blues (113, 127, 143 and 179), all of them published in Claraboya and La Estafeta Literaria.

The translation changed a few words to avoid possible censorship. For example, in chorus 113, the verses “Got up and dressed up; and went out & got laid,” are translated in a less sexual way as “went out & lay down” (Me levanté y me vestí; y salí a la calle y me tendí). Nevertheless, the decontextualized scenes of the poems were not generally a problem for censorship.

1975: En la carretera (On the road). Produciones Editorial. Translator: Horacio Quinto.

Produciones Editorial published Star Books, a collection dedicated to the publication and dissemination of the 1960s counterculture, which introduced writers like Jack Kerouac or Williams S. Burroughs to Spain.

1975: Visiones de cody (Visions of Cody). Barcelona, Editorial Grijalbo. Translator: Marcelo Covian.

This edition of Visions of Cody had a lot of problems, as censorship hampered it on several occasions. The censorship reports show some aspects of the work are considered “morally despicable, typical of the crazy discouraging and feverish life of the American Beatniks, who introduced concepts and ideas as harmful as drugs, drinking as liberation of man, indiscriminate sexual freedom, etc.” The report also says there are scenes with “dialogues and expressions tremendously rude, with a foul vocabulary, and an abuse of foul language” and “descriptions of a pornographic nature and religious irreverence.” Finally, the report indicates the book could have a devastating impact on young people. The 8000 copies of the book were exported to Latin America.

In 1977, the publisher tried selling 4000 copies in Spain and, this time, the work was not censored.

1977: El libro de los sueños (Book of Dreams). Barcelona, Producciones Editorial. Translator: Alvarez Flores.

1975: Jack Kerouac: biografia de una generación. Silvester Wish: Barcelona, Producciones Editoriales.

1980: Poemas dispersos (Scattered Poems): Madrid, Visor Libors. Translator: Mariano Antolin.

1980: En el camino (On the Road). Barcelona, Editorial Bruguera. Translator: Martín Leníndez.

1981: Los vagabundos del Dharma (The Dharma Bums). Barcelona, Editorial Bruguera. Translator: Mariano Antolín Rato.

In the early 1980s, Jack Kerouac’s publications began proliferating in Spain. The Anagrama publishing house was in charge of its dissemination. Some of these publications collected the Latin American translations. His are the editions of The Subterraneans (1986, translated by Rodolfo Wilcock), On the Road (1989, translated by Martín Lendínez), The Dharma Bums (1996, translated by Mariano Antolín Rato), and Vanity of Duluoz (1996, translated by Mariano Antolín Rato).

The Reception and Legacy of Jack Kerouac in Spain

Although Kerouac did not enter Spain until later, he was an especially influential author in the Spanish counterculture. Kerouac’s rejection of bourgeois values served as an inspiration to young people who opposed the dictatorship, and many Spanish authors greatly admired Kerouac and the rest of the Beat Generation. Take for example, the novelist and poet Ignacio Aldecoa, whose fascination with these writers came with a trip to the United States in 1958. After his return, Aldecoa dedicated himself to giving lectures and recitals on American authors, reading fragments of their works and On the Road until its publication in Spain.

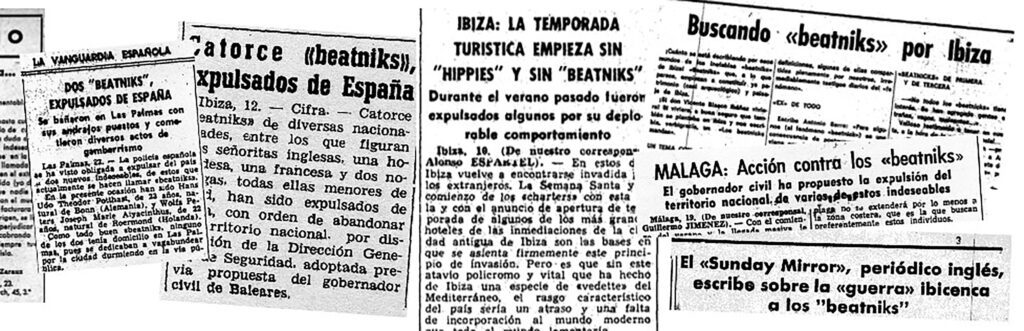

Articles from the newspaper La Vanguardia reporting on the Beatniks in Ibiza and their scandalous way of life. Some of the headlines: “Fourteen Beatniks expelled from Spain,” “Looking for Beatniks in Ibiza,” ”Málaga: Action against the Beatniks.”

"Malú,” a song inspired by Beat Generation poems by Eclipse y Carlos Oroza (click to play video). The song says: “Come, go, fly, leave the dream, cross the line, go through the sound (...) you can go out, you can be, you can enter through the street, you can stand up.” It is a song that incites rebellion and is reminiscent of Ginsberg’s Howl.Aldecoa also helped spread the Beatnik culture in Ibiza, one of the Balearic Islands where the writer used to spend the summer and a popular tourist location for Americans. In that kind of paradise, some small colonies arose that adopted the way of life of Beats, something upon which the Franco regime frowned.

But Aldecoa was not the only who was fascinated by Kerouac and the Beat Generation. In general, during the 1960s, when these authors began to be published, literary critics praised them.

Poet, novelist and journalist Franscico Umbral wrote good reviews about these authors and other writers, like Labordeta, admitted the Beat Generation’s influence.

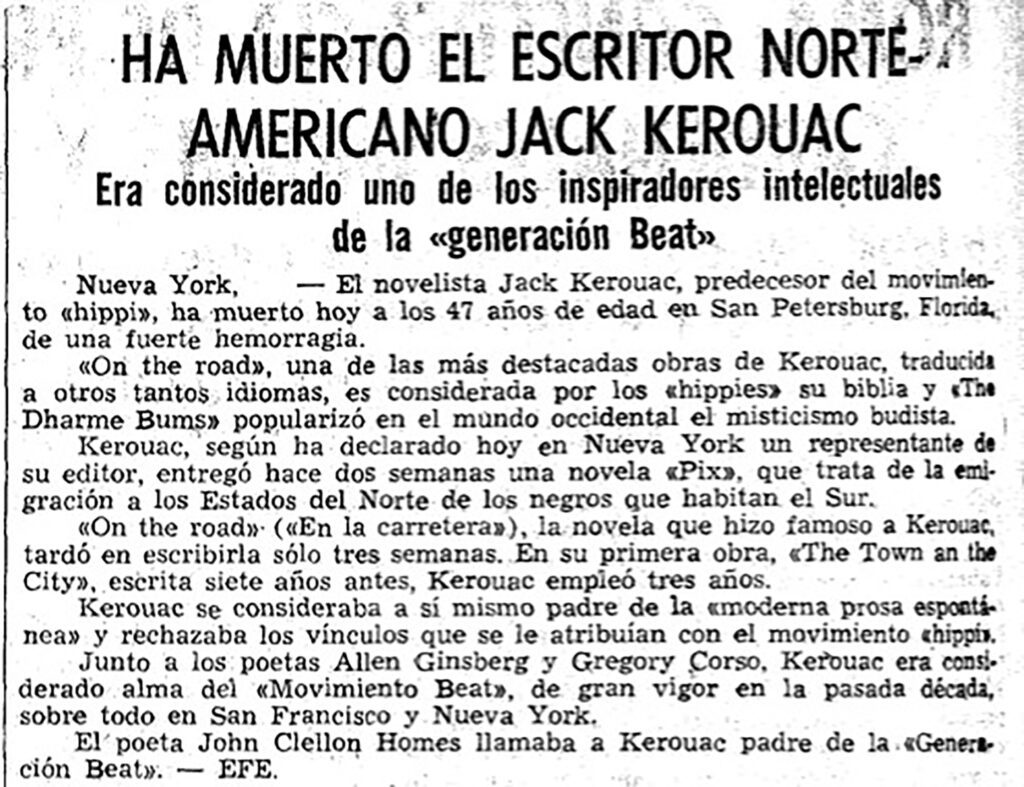

La Vanguardia, October 24, 1969. “North American writer Jack Kerouac has died. Novelist Jack Kerouac, predecessor of the ‘hippy’ movement, died today at the age of 47 in St. Petersbug, Florida, from a heavy hemorrhage. On the Road, one of Kerouac’s most outstanding works, translated into as many languages, is considered by hippies his bible, and The Dharma Bums popularized Buddhist mysticism in the Western world.”With Kerouac’s death, numerous accolades and tributes appeared in newspapers and magazines dedicated to him.

Jack Kerouac’s arrival in Spain was late due to the heavy censorship and cultural repression. However, Kerouac entered the culture and fanned the flame that has never been quenched, though dimmed by fear. Kerouac arrived just in time to infuse the young generation with the necessary encouragement to continue fighting for freedom and democracy. Currently, his figure is still alive in Spain, where, as in the rest of the world, he continues to be an icon of mass culture and his books are still being published. In 2019, Anagrama, the publisher that has his rights, published a special 50th anniversary edition of Kerouac’s best publications, including On the Road as one of its most important published books.

Anagrama’s 50th anniversary commemorative edition of On the Road (2007).

About the Author

A student of Sociology and Political Science at the University of Valencia, and previously at the University of Kent (Canterbury, UK), Carles Albert Boluda focuses on urbanism and city studies, literature, and gender studies.

![<em>Meditteráneo</em> headline: There is a strange world: “Beatniks,” “Hippies,” “Ye-yés” [this is what the Beatniks were called in Spain]. Adolescence walks in a curved line.](https://jackkerouac.org/wp-content/uploads/cache/MeditteraneoHeadlines-scaled/3897523490.jpg)